Sale of the Historical Lebanese “Beiteddine Saraya” to the Ottoman Empire

(1865)

Via the Bkerke Archive

بيع “سرايا بيت الدين” التاريخية إلى السلطنة العثمانية

(1865) من خلال أرشيف بكركي

Dr. Marc Abboud[1]

د. مارك عبود[2]

Abstract

This research – based on an Arabic[3] historical document – reveals the process by which the ownership of the Beiteddine Saraya shifted to the Ottoman Empire. This Saraya represents an important edifice in Lebanon’s history; encapsulating pivotal moments of Emir Bashir Shihab II’s reign over the Lebanese Emirate. In this context, this research article provides insight into the legal and administrative aspects that shaped this sale process framework, while shedding light on the applicable traditions and regulations concerning property sales transactions during the Mutasarrifate era.

Keywords: Ottoman Empire, Lebanon, Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Beiteddine Saraya, Emir Bashir Shihab II, Sitt Husun Jihan, Dawud Pasha, Sale Transaction, Women in the Ottoman Era, Women and the Ottoman Law, Ottoman Contracts, Politics and Economics in the Ottoman era.

الملخص

يُبرز هذا البحث المُرتكز على وثيقة تاريخية مكتوبة باللغة العربية، كيفية انتقال ملكية سرايا بيت الدين إلى السلطنة العثمانية. حيث تُعدّ هذه السرايا معلمًا مهمًّا في تاريخ لبنان، حيث حملت في طيَّاتها أسرار حياة وحكم الأمير بشير الثاني الشهابي الكبير للإمارة اللبنانية. وفي هذا السياق، يُقدّم هذا المقال البحثي معلومات قيّمة حول النواحي القانونية والإدارية التي شكَّلت إطار عملية البيع هذه، مُبيّنًا التقاليد والأنظمة المُتبعة خلال فترة المتصرفية في صفقات بيع العقارات.

الكلمات المفاتيح: السلطنة العثمانية، لبنان، متصرفية جبل لبنان، سرايا بيت الدين، الأمير بشير الشهابي الثاني، الست حسن جهان، داود باشا، صفقة بيع، النساء في العهد العثماني، النساء والقانون العثماني، العقود العثمانية، السياسة والاقتصاد في العهد العثماني.

Introduction

After conducting a meticulous and thorough search in the Maronite Patriarchate’s Archives at the Monastery of Bkerke[4], an important historical document[5] was unearthed from Patriarch Elias Howayek’s[6] archives.

This historical document reveals the specifics of the sale of Beiteddine[7] Saraya[8], which currently serves as the summer residence for the President of the Lebanese Republic. The historical document provides valuable insight for researchers on the Lebanese history, and showcases the real estate and administrative system during the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate[9] era.

Throughout history, many great historical figures have been accustomed to building magnificent architectural buildings to manifest their power, prestige, and culture. These buildings may range from palaces, temples or memorials not only as marvels of refined architectural design, but also as embodiments of the vision and aspirations of those who commissioned them.

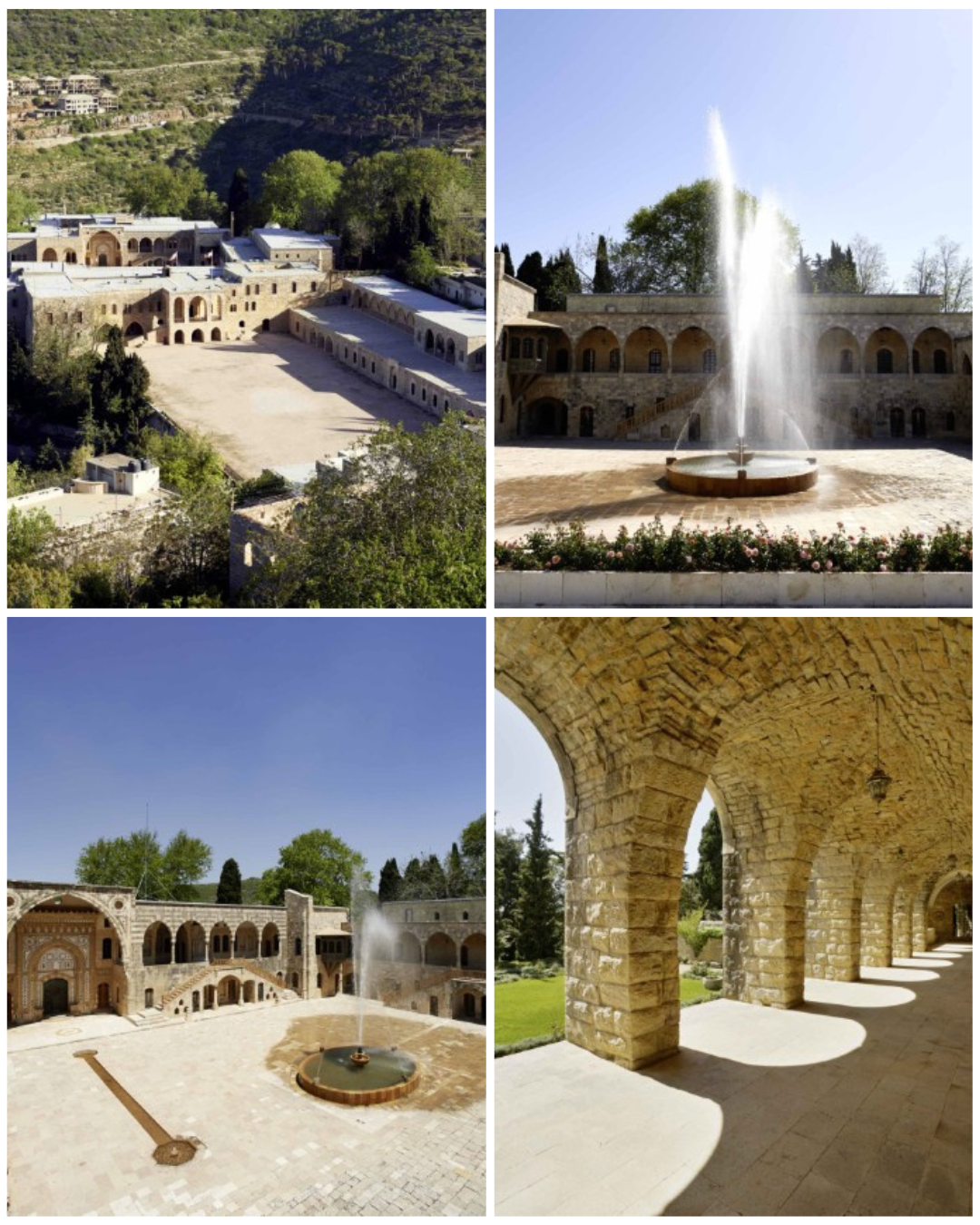

After establishing his rule, Emir Bashir Shihab II[10] initiated the construction of a new Saraya[11] at the Beiteddine Village in 1808; he recruited brilliant Italian builders and architects and entrusted them with building a Saraya, blending Turkish elegance with Italian artistry, and the construction was completed in a span of about seven years. Beiteddine Saraya remained the seat of the Shihab Emirate until 1840, a year that marked Emir Bashir’s exile to Malta[12]. After Emir Bashir’s death, this Saraya became the property of his widow, the Circassian “Sitt Husun Jihan bint Abdullah”, who was his second wife.

Sitt Husun Jihan was a beautiful Circassian young woman brought to the Emir from Istanbul after the death of his first wife, the mother of his sons; and the Emir married Sitt Husun Jihan and had a profound affection for her at the time. When the Emir was getting old, the new bride seized control over the Emir’s entourage; to the point that the Chief of the Scribes “Master Boutros Karami” cynically nicknamed him “Abu Saada” after the name of the first daughter he had from his wife Sitt Husun Jihan[13].

After the dissolution of the Shihab Emirate and the establishment of the Qa’immaqamaytain[14] System, and then the subsequent onset of the “Mutasarrifate” following the 1860 events, the Ottoman Empire – represented by the Mutasarrif Dawud Pasha – harbored intentions of procuring the Beiteddine Saraya from Sitt Husun Jihan; in order to convert it into a summer headquarters for the Mutasarrifs.

In this historical research, our quest will be to unravel: How was the Saraya’s schematic segmentation? What are the legal procedures followed in its sale? And what was the value of this important historical palace?

Key Information mentioned in the Sale Process

- Location of Beiteddine Saraya and its architectural layout

Beiteddine Saraya is located in the Al-Manasif Directorate[15] and lies in close proximity to Deir El-Qamar village[16] situated on the picturesque slopes of Mount Lebanon. Emir Bashir’s name became associated with the Beiteddine Saraya, including all its facilities and annexes with every facet, nook, and cranny of the Beiteddine Saraya inclusive of its myriad facilities and extensions. Bearing the imprints of his legacy is the Harem Wing (Dar Al-Hareem)[17], which encompasses lower and upper locations from houses, rooms, courtyards, toilets and utility rooms, starting from a large door inlaid with marble extending in every direction until its very last wall.

The Saraya’s architectural marvel features a Central Wing (Dar Al-Wusta), comprising a large running water pond, Pavilions (Ewan), halls, Diwan Khans[18], squares, courtyards, small rooms, water basins, spaces, toilets and utility rooms. This Wing also sports an Upper Wing known as the Diwan Khan Wing, containing an Ewan, Diwan Khan, three squares, a room, a running water standpipe, and a tiled open-air courtyard accessible through an ascending stone stairway leading from the courtyard of the Central Wing. It also includes a Lower Wing known as the Horses’ Wing (Dar Al-Khail), harboring an Ewan, rooms, two running water ponds, an open-air courtyard, a dry-stacked stone and mortar vault, where one is made of dry-stacked stone, while the other is an open-air vault; in addition to toilets, stables, two rooms, a hayloft, dry-stacked stone barns located below the aforementioned the Harem Wing, dry-stacked stone granary vaults located below the aforementioned Central Wing; and it is also adorned with three lush gardens showcasing diverse flora and a communal lavatory facility comprising rooms, an Outer Hall (Barrani), a Middle Hall (Wastani) and a water basin, with all that connects to it in whole and in part.

- Sitt Husun Jihan’s Acknowledgement of the Saraya’s Sale

Sitt Husun Jihan acknowledged that on the 17th of February 1865, she had sold what she owned – in her legal capacity[19] – and that she had divested her ownership rights to the esteemed Mount Lebanon Mutasarrif, Dawud Pasha; the appointed representative of the Ottoman Empire. This entails the legal sale of the Beiteddine Saraya, including all and part of the storage areas and lands connected thereto, for the sum of two thousand and five hundred sacks, with each sack holding five hundred piasters, completely received “by hand”, including their excess consular papers; and so she relinquishes any further claims or entitlements that are related to the sale process or stipulated sum.

In light of the above, a detailed Legal deed (Hijja Shariiya)[20] was drafted, signed and sealed by his Eminence (Fadilat)[21] Sharif Rushdi Effendi, the presiding Judge of Beirut, and Sitt Husun Jihan wrote this bond affirming her recognition of the deed in its entirety.

- Witnesses

After the Council had reviewed the contents of this deed, both Emir Salim Abdullah Shihab, who was the husband of Saada, daughter of Emir Bashir Shihabi II, i.e. the son-in-law of Sitt Husun Jihan[22], and Khawaja Sarkis bin Youssef Al-Bayrouti, attended; as they bore witness to Sitt Husun Jihan’s affirmation regarding the authenticity of all the sales detailed within the deed. They further attested that the sale, as chronicled in the deed, to His Excellency “Devletlû[23] Mount Lebanon Mutasarrif Dawud Pasha” on the stipulated month on behalf of the “Supreme Ottoman Empire supported by God Creator of All Creatures (Barii Al-Bariah)[24]”, was according to the agreed sum of two thousand and five hundred sacks; and was fully dispensed from the Supreme Empire’s funds in the buyer’s country.

They confirmed her declaration of relinquishing any further claims or entitlements related to the aforementioned Saraya, and that she has nothing more to do with it in regards to any possessions or its determined value. They also testified to Sitt Husun’s acknowledgement that the Saraya as described in this valid contract had transitioned into the sole possession of the Supreme Empire, which will manage it as it deems fit, and that she had dropped the Ghobn[25] and Gharar[26] lawsuits, should they arise. Based on her testimony and statement before the Council, the contract was duly ratified and inscribed in the Council’s register in accordance with the regulations. This contract was finalized on the 17th of February 1865.

- Beiteddine Saraya’s Sale Bond

In line with all the procedures pertaining to the sale process, the Noble Legal Council and Sublime Ruling Assembly (Majles Alsharii Alshareef Wa Mahfal Alhukm Almuneef)[27] was held by the Hanafi Judicial Authority, “Sharif Rushdi Effendi Sidqi Zadeh”, at the residence located in the Jiyeh village[28] situated within the Directorate of Eklim Al-Kharoub[29]; at the house of the Circassian Sitt Husun Jihan bint Abdullah. Her identity was vouched for by Emir Salim, son of Emir Abdullah Shihab, and Priest Youssef bin Youssef Farah. They both unequivocally recognized Sitt Husun, noting specifically that her face was not covered. Sitt Husun Jihan presented the legal deed verifying her ownership of the Saraya that she inherited through legitimate donation (Heba) and purchase (Shira’a)[30] from her husband, the deceased Emir; and that was in the form of two legal documents in her possession.

Pursuant to the Royal Order (Amer Sami)[31] issued by the Supreme Ottoman Empire (Al-Dawla Al-Aliya)[32], the Administrative Mount Lebanon Mutasarrif, Dawud Pasha, was authorized to purchase the “Beiteddine Saraya” from Sitt Husun Jihan, this purchase would be financed through the Ottoman Empire’s dedicated funds.

On the 19th of February 1865, the sale bond was officiated by Beirut Court’s deputy, Mr. Ibrahim bin Ali Al-Ahdab, and Sitt Husun Jihan. Upon sealing the deal, Sitt Husun Jihan received the sum, stipulated as two thousand and five hundred sacks, each containing five hundred piasters of the Miri currency[33], based on her acknowledgement and it was done in a complete, adequate, and satisfactory due diligence manner that denies any type of ignorance (Anwah Al-Jahala)[34], while acknowledging her knowledge (Al-Khubra)[35], prior inspection (Muayanat)[36] and previous examination; Furthermore, any potential Ghobn and Gharar disputes initiated by either party were nullified. and so, the bond concluded the necessity of the sale by choice (Luzum Al-Mubih Bel Al-Ekhtiyar)[37]. Afterwards, during the appeal process, Al-Sitt Husun Jihan completely discharged (Ibraa Zimma)[38] the Mutassarif of all rights, lawsuits and requests related to the sale, sold items and price; thereby dropping all other legitimate rights; and such discharge had been legitimately accepted by the Honorable Mutassarif, i.e. the aforementioned authorized representative, in person.

Any ramifications or contingencies from the Sale Guarantee (Durk)[39] or Dependence (Tabaeeya)[40] will fall on the seller; as the guarantee must be legitimate. This was further endorsed by formally recording all discussed stipulations in the official register. The bond was scrupulously curated after considering all the law’s legitimate requirements. As for the present witnesses (Shohoud Al-Hal)[41], they were Emir Salim Abdullah Shihab, Priest Youssef bin Youssef Farah, Khawaja Sarkis bin Youssef Al-Bayrouti, and others.

Conclusion

The aforementioned assessment of the Beiteddine Saraya transaction during the Mutasarrifate era under Ottoman rule offers an enriching perspective on various facets of historical significance:

- Economic Value: The Saraya was sold for 2500 sacks, where each sack contained 500 piasters. This gives an idea about the property’s economic value during that era serve as a reflection of the broader economic landscape of the region at that time, and the influence of Ottoman policies on regional economic activities.

- Sitt Husun Jihan: She was Emir Bashir’s widow, the prominent role of Sitt Husun Jihan in this sale process. despite the challenges and conventional perceptions of women’s roles in Middle Eastern societies during the Ottoman era in real estate and political affairs at the time, which is sometimes rare in the oriental history. This role gives a general idea about the social and legal status of women during the Ottoman period, especially in handling the property and inheritance matters; which may result in reconsidering the conventional understanding of the women’s role in the oriental communities at that time.

- Architectural Details: The article shows the meticulous detailing of the Saraya’s architectural attributes, such as ponds, halls and headquarters. This contributes to shedding light on the socio-cultural and priorities pertaining to the historical period in which the Saraya was built.

- Legal documents: the extensive documentation and rigorous detailing of the sale process underscore the Ottoman Empire’s commitment to procedural robustness. This intricate legal framework serves as a testament to the advanced nature of the Empire’s legal system, ensuring transparency, fairness, and fostering trust.

- Transaction Participants: The historical document shows the parties involved in the transaction; which gives an idea about the political and economic relations between the various parties, and highlights how negotiations and agreements are made on such major transactions.

At the end of this article, which highlighted an important aspect of the history of Lebanon and the Ottoman Empire by focusing on the Beiteddine Saraya, we find that the historical document that has been used clearly shows the legal and administrative process that led to the transfer of ownership of this historical landmark. The research was not only limited on this matter, but also shed light on the Saraya’s architectural details and the leading figures who were part of this transaction.

In light of the document that has been relied upon, it is imperative to highlight the Ottoman Empire’s decision to respect property rights and proceed with a legally sound purchase, rather than a unilateral confiscation following Emir Bashir’s exile to Malta; instead, it opted for a path filled with legal and legitimate proceedings, by procuring the Saraya through a purchase from the Emir’s widow. This raises an important question: Was this tolerant behavior an adopted policy throughout the Ottoman Empire during that period? The answer to this question remains open, thereby encouraging researchers to explore more dimensions in this context.

Appendix

Beiteddine Saraya. Presidency of the Republic of Lebanon. Retrieved October 13, 2023, from http://www.presidency.gov.lb/English/PresidentoftheRepublic/PresidentialPalaces/Pages/BeitElDinPalace.aspx

Sources and References:

- Abd Al-Karim Bin Ali Bin Muhammad Al-Namlah, Al-Muhazib fi Eilem Usul Al-Fiqh Al-Muqarin, Al-Rushd Library for Publishing and Distribution, Riyadh, 1999.

- Abdallah bin Trad Al-Beiruti, Mokhtasar Tarikh Al-Asakifa Allazin Rako Martabat Reasat Al-Kahnout Al-Jalila Fi Madinat Beirut, Dar An-Nahar for Publishing, First Edition, Beirut, Lebanon, June 2002.

- Abdellatif Fakhoury, Ayam Beirutiya (15): Waqf Qasr Beiteddine Li-Himayatoh Men Al-Mosadara Soma Ebtal Al-Waqf Li-Subut Al-Heba Kabl Al-Waqf, Al-Liwaa Newspaper, 17th of February 2020.

- Abdullah Al-Mallah, Bayn Al-Bateriyark Elias Al-Howayek wa Muzafar Bacha, Al-Manara Magazine, Issue No. 3, 1996.

- Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo, Al- Moajam Al-Wasseet, Al-Da’wah Publishing House. P. 2/628.

- Adel Sharif and Mahmoud Rabih Khater, Al-Wafi fi Siyagh Al-Da’wi Wa Al-Oukoud, Dar Mahmoud, Cairo, 2021-2022.

- Ahmed Mokhtar Omar, Moajam Al-Logha Al-Arabia Al-Moasira, First Edition, Alam Al Kotob, Cairo, 2008.

- Ahmed Mukhtar Abdel Hamid Omar, Moajam Al-Logha Al-Arabia Al-Mouasira, Alam Al-Kotob, First Edition, 2008.

- Ahmed Youssef Al-Qurmani, Akhbar Al-Duwal wa Asar Al-Awwal, Part Two, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Beirut.

- Al-Sayyid Sabiq, Fiqh al-Sunnah, Part Three, Al-Fateh for Arab Media, Cairo.

- Al-Siddiq Muhammad Al-Amine Al-Darir, Al-Gharar wa Assaroh Fi Al-Oukud Fi Al-Fiqh Al-Islamy, Second Edition, Khartoum, 1995.

- Amine Khoury, Rafiq Al-Othmani, Al-Adab Press, Beirut, 1894.

- Bkerke’s Archives, Patriarch Elias Howayek’s File No. 28, Historical Document No. 27.

- Elia Harik, Al-Tahawol Al-Siyasi Fi Tarikh Lubnan Al-Hadiss, Al-Ahlia for Publishing and Distribution, Beirut, 1982.

- Elias Matar (the book is translated from Turkish into Arabic), Shareh al-Majalla, First Edition, 1880.

- Emad Murad, Al-Adyira Fi Kadaa Keserwan – Nabza Tarikhiya – Selselt Adyiret Lubnan 2.

- Emile Yacoub, Al-Moajam Al-Mofasal Fi Al-Joumouh, First Edition, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2004.

- Ibn Manzur, Lisan Al-Arab, Dar Al-Maaref, Cairo.

- Ibrahim Al-Aswad, Dalil Lubnan, Third Edition, Ottoman Printing Press, Lebanon, 1906.

- Ismat Abd Al-Majeed Bakr, Al-Madkhal Li-dirasat Al-Nezam Al-Kanouny Fi Al-Aahdayn Al-Othmani Wa Al-Jomhori Al-Turki, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2012

- Jalal Al-Din Al-Mahali and Jalal Al-Din Al-Suyuti, Tafsir Al-Jalalain Be-Hamish Al-Quran Al-Kareem, Al-Aasriya Library, Lebanon, 2012.

- John Lewis Burckhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land, the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the interior parts of Africa, London, 1822

- Marc Abboud, Al-Motran Boutros Shibli (1870-1917) Rahi Abrashiyat Beirut Al-Marouniya, Postgraduate Diploma Thesis, Lebanese University, Beirut, 2014.

- Muhammad Amim Al-Eḥsan Al-Mujaddadi Al-Barkati, Al-Taarifat Al-Fiqhiya, First Edition, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2003.

- Muhammad Bahr Al-Ulum, Ouyub Al-Eirada Fi Al-Shariah Al-Islamia, Second Edition, Al-Alfain Bookshop Company, 2001.

- Muhammad bin Salih Al-Uthaymi, Tafseer Al-Quran Al-Kareem – Juzuu Aam, Second Edition, Dar Al-Thuraya Publishing, 2002.

- Muhammad Hadi Al-Shamrakhi Al-Mardini, Sharh Al-Allama Al-Shaykh Muhammed Bin Qasim Al-Ghazzi Al-Mosama Fateh Al-Qareeb Al-Mujib Fi Sharh Alfaz Al-Takreeb Lel Imam Al-Allama Ahmed Bin Al-Hussein Al-Shahir bi Abu Shujaa. Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2016.

- Muhammad Omar Dawud Abu Hilal, Al-Jahala Wa Asarha Fi Al- Da’wah Al-Qadaiya, Academic Book Center, Al-Quds University, 2013.

- Muhammad Rafi Salem Ali, Tawabii Al-Mubii Wa Kawaidha Al-Fiqhiya, Al-Mukhtar Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 39, No. 1, Libya, 2021.

- Nasif Al-Yaziji, Risala Tarikhiya Fi Ahwal Jabal Lubnan Al-Iktaii, Dar Maan.

- H. Collin, Dictionary of Law – 8000 TERMS CLEARLY DEFINED, Fourth Edition, BLOOMS BURY, London , 2004.

- Reinhart Pieter Anne Dozy, Takmelat Al-Maajim Al-Arabiya, First Edition, Ministry of Culture and Information, Republic of Iraq, 1979-2000.

- Saadi Dannawi, Al-Moajam Al-Mofasal fi Al-Muarrab wa Al-Dakheel, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Arabiya, Beirut, 2004.

- Sobhi Suleiman, Fan Al-Taamul Maa Al-Diplomasiyin, Arab Press Agency (Publishers), Egypt, 2019.

- Taqi Al-Din Ahmad bin Taymiyyah Al-Harrani, Majmouaat Al-Fatawy – Kitab Al-Kadar, Part Eight.

- The Encyclopedia Britannica Volume 12, Eleventh Edition, Cambridge, England: at the university Press, New York, 1910.

- Tony Mfarrej, Mawsuaat Koura wa Modon Lubnan, Part Five, Dar Nobilis, Beirut.

- Toubiya Al-Oneissi Al-Halabi Al-Lubnani, Kitab Tafseer Al-Alfaz Al-Dakhila fi Al-Logha Al-Arabiya Maa Zikr Aslaha Bihurufih, Second Edition, Egypt, 1932.

- Youssef Yazbeck, Al- Juzur Al-Tarikhiya Lel Harb Al-Lubnaniya Men Al-Fateh Al-Othmani Ila Bourouz Al-Kadiya Al-Lubnania, Dar Nawfal, Lebanon, 1993.

[1]– Ph.D. in History| Entrepreneur | Human Development Trainer | Consultant | Sworn Informatics Expert in Lebanon.

–[2] دكتور في التاريخ | رجل أعمال | مدرّب تنمية بشريّة | مستشار | خبير معلوماتية محلّف لدى المحاكم اللبنانية.

[3]– Various terms and references in this article were transcribed to reflect their phonetic pronunciation in the original Arabic language.

[4]– Monastery of Bkerke: In 1720, during the leadership of Patriarch Yacoub Awad, the Antonin monks procured the Monastery of Bkerke from the Cheikhs of El-Khazen. Subsequently, they expanded it, elevating it to one of Keserwan’s most significant monasteries. By 1750, a significant disagreement arose between the monks and the Cheikhs, Khazen and Junaid El-Khazen. Intervening in this matter, Archbishop Germanos Sakr Al-Halabi, accompanied by Archbishop Toubia El-Khazen, opted to purchase the Monastery, so that Nun Hindiyya will establish her monastic order; in turn, she completed the construction of the Monastery in a new style and distinctive architecture in 1752 and established her order until she was removed from it. In 1790, the Synod at Bkerke designated this monastery as the Maronite Patriarchs’ headquarters. Emad Murad, Al-Adyira Fi Kadaa Keserwan – Nabza Tarikhiya – Selselt Adyiret Lubnan 2, PP. 428 – 431.

[5] Bkerke’s Archives, Patriarch Elias Howayek’s File No. 28, Historical Document No. 27.

[6] Patriarch Elias Howayek: He was born in Halta in Batroun District in late December 1843. He learned the primary principles at the village school and at St. Youhanna Maroun Kfarhay School. He then entered the Jesuit Fathers’ School in Ghazir, and was sent by Patriarch Boulos Massad (1854-1890) to the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith School in Rome, where he completed his studies and ordained a priest. upon returning to Lebanon in 1870, Patriarch Massad promoted him to the bishopric rank on the 14th of December 1889. On the 6th of January 1899, the Bishops Synod elected him patriarch for the Maronite Church. After a long struggle in serving the Church and the nation, Patriarch Howayek passed away in 1931. Abdullah Al-Mallah, Bayn Al-Bateriyark Elias Al-Howayek wa Muzafar Bacha, Al-Manara Magazine, Issue No. 3, 1996, P. 449

[7] Beiteddine village: A historic town in the Chouf district situated on a hill overlooking Deir El-Qamar. It is located at an average altitude of 850 m above sea level and 45 km away from Beirut, with a total land area of 285 hectares. The name may be of an ancient Semitic origin, which means: a courthouse; as people believe that the place used to be an ancient courthouse. This village includes the families of: Al-Khoury, Abou Khalil, Chkaiban, Najm, Wehbe, Deeb, and Zidan. Tony Mfarrej, Mawsuaat Koura wa Modon Lubnan, Part Five, Dar Nobilis, Beirut, PP. 179 – 188.

[8] Saraya: The King’s Court or Palace. its roots trace back to the Persian word “Saray”, which means a large high-ceiling house. Saadi Dannawi, Al-Moajam Al-Mofasal fi Al-Muarrab wa Al-Dakheel, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Arabiya, Beirut, 2004, P. 274.

[9] Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate: After 1861, the Mount Lebanon appeared with a new order based on the Statute consisting of 17 articles. The power was then assumed by a non-Lebanese Ottoman Catholic Christian Mutasarrif, provided that an Administrative Council would support him assisted by a diverse 12-member representing various denominations. The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate spanned seven distinct districts, (Batroun, Koura, Keserwan, Matn, Chouf, Jezzine, and Zahlé) and Directorate of Deir El Qamar. Over time, several Mutasarrifs have consecutively assumed the power: Dawud Pasha (1861-1868), Franco Pasha (1868-1873), Rustom Pasha (1873-1883), Wasa Pasha (1883-1892), Naoum Pasha (1892-1902), Muzaffer Pasha (1902-1907), Youssef Pasha (1907-1912) and Ohannes Pasha (1912-1915) who has not completed his term and left the Ottoman capital after Jamal Pasha had come to Lebanon. In the next three years, the country came under Ottoman rule, and Muslim mutasarrifs were appointed, they are: Ali Munif (1915-1916), Ismail Hakki (1916-1918), and Momtaz Bey (1918), whose reign lasted for only 35 days. Marc Abboud, Al-Motran Boutros Shibli (1870-1917) Rahi Abrashiyat Beirut Al-Marouniya, Postgraduate Diploma Thesis, Lebanese University, Beirut, 2014., PP. 27-28.

[10] Bashir Shihab II: He was born in 1768, and took over the Mount Lebanon Emirate, and then he was dismissed several times by Ahmed Al-Jazzar Pasha and his successors in the Acre Governorate. Each dismissal came with a latent promise of reinstatement; often tethered to increased taxation demands. Until a Royal Ferman was issued stating the appointment of Bashir III as his successor, and the Emir left the country to Malta, and later settled in Astana, where he passed away on the 29th of December 1850. Abdallah bin Trad Al-Beiruti, Mokhtasar Tarikh Al-Asakifa Allazin Rako Martabat Reasat Al-Kahnout Al-Jalila Fi Madinat Beirut, Dar An-Nahar for Publishing, First Edition, Beirut, Lebanon, June 2002, P. 113.

[11] John Lewis Burckhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land, the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the interior parts of Africa, London, 1822, P. 192.

[12] Tony Mfarrej, Ibid., Part Five, 2021, PP. 182 – 184.

[13] Emir Bashir, following traditional naming customs, must be called “Abu Qasim”, which means “father of Qasim.” This title comes from the name of his eldest son, Qasim, from his first marriage. Youssef Yazbeck, Al- Juzur Al-Tarikhiya Lel Harb Al-Lubnaniya Men Al-Fateh Al-Othmani Ila Bourouz Al-Kadiya Al-Lubnania, Dar Nawfal, Lebanon, 1993, P. 234.

[14] Qa’immaqamaytain: After the end of the Shihab era, with the cooperation between the Ottoman Empire and the European countries, Lebanon underwent an administrative reconfiguration, segmented into two Qa’immaqamaytain (Two Districts); as the first was ruled by a Druze Qa’immaqam (District Governor), while the second by a Maronite one. This bifurcation, however, sowed seeds of discontent due to significant Maronite populations residing in the Al-Qa’immaqamiyya Al-Darziya (Druze District), and a significant Druze population in the Al-Qa’immaqamiyya Al-Maroniyya (Maronite District). Elia Harik, Al-Tahawol Al-Siyasi Fi Tarikh Lubnan Al-Hadiss, Al-Ahlia for Publishing and Distribution, Beirut, 1982, P. 39.

[15] Al-Manasif Directorate: Named for its central positioning and moderate climate. It stretches from the Beiteddine Valley to the Qadi Bridge. Deir El-Qamar is considered its headquarters, and the Directorate’s villages include Bchetfine, Kfarqatra, Kfarhim, Kfarfakoud, Sirjbal and Jahlieh. Nasif Al-Yaziji, Risala Tarikhiya Fi Ahwal Jabal Lubnan Al-Iktaii, Dar Maan, P. 12.

[16] Deir El-Qamar village: It is considered the most famous mountain town in modern Lebanese history; since it was the capital of the Lebanese Emirate and had witnessed numerous pivotal historical events throughout its reign. It is located to the southeast of the capital of the Lebanese Republic; i.e. Beirut, in the heart of the Al-Manasif region in the Chouf district, occupying a rectangular elevation whose long sides extend from the east to the west, while being situated in the south of the valley separating Baakline and Beiteddine, at an altitude of 850 m above sea level, with a land area of 775 hectares. Its name came from the inspiration from a lunar emblem engraved on a stone, which even today embellishes the southern facade of the Church of Saydet al Talle. Elia Harik, Ibid., P. 212.

[17] Dar Al-Hareem: This term commonly refers to the section of a house in certain oriental countries reserved exclusively for women. The Encyclopedia Britannica Volume 12, Eleventh Edition, Cambridge, England: at the University Press, New York, 1910, P. 950.

[18] Diwan: It is the place designated for the State matters and the government issues are handled. Khan: signifies a prince and the master. This means that the Diwan Khan Wing (Emir’s Headquarters) is the place that the Emir regards as a headquarters to rule the State. Toubiya Al-Oneissi Al-Halabi Al-Lubnani, Kitab Tafseer Al-Alfaz Al-Dakhila fi Al-Logha Al-Arabiya Maa Zikr Aslaha Bihurufih, Second Edition, Egypt, 1932, P. 23. and Emile Yacoub, Al-Moajam Al-Mofasal Fi Al-Joumouh, First Edition, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2004, P. 182.

[19] Legal capacity: refers to the ability to enter into a legally binding agreement, which is one of the essential elements of a contract. It is typically associated with a person of full age and of sound mind, making them eligible to enter into a contract. P.H. Collin, Dictionary of Law – 8000 TERMS CLEARLY DEFINED, Fourth Edition, BLOOMS BURY, London, 2004, PP 40 and 150.

[20] Hijja Shariiya: evidence and proof. In this context, it means a deed asserting ownership; i.e. any sale deed, or a bond proving the right to ownership transfer. Ahmed Mokhtar Omar, Moajam Al-Logha Al-Arabia Al-Moasira, First Edition, Alam Al Kotob, Cairo, 2008, P. 445.

[21] Fadilat: It is the term used to address and refer to Islamic religious scholars who occupy prominent positions, such as judges. It is even used to address and refer to the State Mufti in some Arab countries. Typically, one might say “Fadilat Al-Sheikh”, or “Fadilat” followed by the name of a particular scholar. Additionally, Fadilat signifies a high degree of virtue. In this context, virtue stands as the antonym of flaw and vice, suggesting a man of high moral standing. Sobhi Suleiman, Fan Al-Taamul Maa Al-Diplomasiyin, Arab Press Agency (Publishers), Egypt, 2019, P. 78.

[22] Abdellatif Fakhoury, Ayam Beirutiya (15): Waqf Qasr Beiteddine Li-Himayatoh Men Al-Mosadara Soma Ebtal Al-Waqf Li-Subut Al-Heba Kabl Al-Waqf, Al-Liwaa Newspaper, 17th of February 2020.

[23] Devletlû: This is an Ottoman term denoting the “Governor of the State”. Amin Khoury, Amine Khoury, Rafiq Al-Othmani, Al-Adab Press, Beirut, 1894, P. 145.

[24] Barii Al-Bariah: The name “Barii” (meaning “Creator”) is mentioned in the Holy Quran in the Verse “Moses said to his people, ‘My people, you have wronged yourselves by worshipping the calf, so repent to your Creator and kill the guilty among you. That is the best you can do in the eyes of your Creator. He accepted your repentance: He is the Ever Relenting and the Most Merciful” [Al-Baqara, Verse 54]; it signifies that God created humans to worship Him. Another mention is in the verse “He is God: The Creator, the Originator, the Shaper. The best names belong to Him. Everything in the heavens and earth glorifies Him: He is the Almighty, the Wise” [Al-Hasher, Verse 24]; which emphasizes that God created humans from nothingness. Jalal Al-Din Al-Mahali and Jalal Al-Din Al-Suyuti, Tafsir Al-Jalalain Be-Hamish Al-Quran Al-Kareem, Al-Aasriya Library, Lebanon, 2012, PP. 8 and 548.

As for the Word “Al-Bariah”(meaning “Creatures”), it was mentioned in the Holy Quran in the following verses: “Indeed the faithless from among the People of the Book and the polytheists will be in the fire of hell, to remain in it forever. It is they who are the worst of creatures.” [Al-Bayyina, Verse 6], and the following verse “And those who believe and do good, righteous deeds – they are the best of creatures” [Al-Bayyina, Verse 7]; In this context, “Al-Bariah” denotes all creatures. Muhammad bin Salih Al-Uthaymi, Tafseer Al-Quran Al-Kareem – Juzuu Aam, Second Edition, Dar Al-Thuraya Publishing, 2002, P. 279.

The renowned Islamic scholar Imam Ahmad ibn Taymiyyah notably used the phrase “Barii Al-Bariah” when responding spontaneously to a query from another scholar:

“You present a tricky question,

One that challenges God Almighty,

Barii Al-Bariah (Creator of all Creatures).”

Taqi Al-Din Ahmad bin Taymiyyah Al-Harrani, Majmouaat Al-Fatawy – Kitab Al-Kadar, Part Eight, P. 149.

Based on the foregoing, the phrase “Barii Al-Bariah” translates to “Creator of all Creatures”, referring to God, and so the phrase “the Ottoman Empire supported by Barii Al-Bariah” was used by the Ottoman Empire in many of its legal documents.

[25] Ghobn: Linguistically, it means “Defraud” for example, he was defrauded; i.e. tricked. As for the jurists, they defined Ghobn as “the inequality between what the individual gives and what he takes” or “it is the inequality between the performances in the contract in a manner that disturbs the balance that the two contracting parties have considered; as one of them will take less than what he gives. In this case, the person who gives more than he takes is called the Defrauded, while the person who takes more than he gives is called the Defrauder”. Jurists divided Ghobn into two types: Simple Defraud and Obscene Defraud. Muhammad Bahr Al-Ulum, Ouyub Al-Eirada Fi Al-Shariah Al-Islamia, Second Edition, Al-Alfain Bookshop Company, 2001, P. 297.

[26] Gharar: Linguistically, the term “Gharar” in Arabic signifies danger. The esteemed Judge “Ayyad” stated that the linguistic origin of “Gharar” is something that appears attractive externally but is detestable internally. This is why the worldly life is termed “metāʿ al-ghurūr” (deceptive enjoyment). He added that it might be derived from “Al-Ghrāra,” meaning deception. Therefore, a man can be described as “Ghir” for deception, and the term can also be used for the one who has been deceived.

Gharar is a term derived from “Al-Tagrīr” (Deception). It refers to exposing oneself or one’s wealth to destruction unknowingly. Al-Siddiq Muhammad Al-Amine Al-Darir, Al-Gharar wa Assaroh Fi Al-Oukud Fi Al-Fiqh Al-Islamy, Second Edition, Khartoum, 1995, PP. 47 and 48.

[27] Majles Alsharii Alshareef Wa Mahfal Alhukm Almuneef: this referred to a judicial body or court overseeing religious and customary matters. Historically, these lawsuits were managed by a single judge, and the court didn’t have a dedicated building. It might be held at a location such as the judge’s house, mosque, or school. Eventually, the Ottoman authorities introduced courts with fixed locations and designated buildings. Because of its religious significance, the Majles Alsharii was also known as “Noble Legal Council” or ” Sublime Ruling Assembly”. Ismat Abd Al-Majeed Bakr, Al-Madkhal Li-dirasat Al-Nezam Al-Kanouny Fi Al-Aahdayn Al-Othmani Wa Al-Jomhori Al-Turki, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2012, P. 95.

[28] Jiyeh village situated in Eklim Al-Kharoub within the Chouf District, 33 km away from Beirut; with a land area of 789 hectares. Its name is of Aramaic origin that means joyful and pleasant place. It includes the families of: Estephan, Badran, Al-Boustani, Abou Saleh and Farhat. Tony Mfarrej, Ibid., Part Nine, PP. 75 – 79.

[29] Eklim Al-Kharoub: Part of the Chouf District, and it includes the villages of Barja, Chhime, Jiyeh, Ketermaya and Mrayjat. Ibrahim Al-Aswad, Dalil Lubnan, Third Edition, Ottoman Printing Press, Lebanon, 1906, P. 34.

[30] Heba: Refers to generously giving to others, whether with money or other means. In Sharia Law, “Heba” is a contract in which a person gives away his possessions to another during his lifetime without expecting any compensation in return.

Shira’a (In Islamic finance or jurisprudence) : It means exchanging one form of money for another based on mutual consent or transferring property with compensation in an authorized manner.

Al-Sayyid Sabiq, Fiqh al-Sunnah, Part Three, Al-Fateh for Arab Media, Cairo, PP. 89 and 266.

[31] Amer Sami: Refers to an authoritative command issued by a monarch or similar authoritative figure, highlighting the status of a king, prince, or equivalent. Ahmed Mukhtar Abdel Hamid Omar, Moajam Al-Logha Al-Arabia Al-Mouasira, Alam Al-Kotob, First Edition, 2008, P. 2/1115.

[32] Al-Dawla Al-Aliya: The Ottoman Empire was referred to by various names in Arabic. One of the most notable is “Al-Dawla Al-Aliya,” an abbreviation for its formal designation, “The Supreme Ottoman State.” In Arab countries, especially the Levant and Egypt, it was called “the Othmalian Empire”, derived from the Turkish word “Othmali”, which means Ottoman. Among the other names added to the Arabic ones are European terms such as “Ottoman Empire”; some also referred to it as the “Ottoman Sultanate” or the “State of the Ottoman Family”. Ahmed Youssef Al-Qurmani, Akhbar Al-Duwal wa Asar Al-Awwal, Part Two, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Beirut, PP. 181 and 182.

[33] Miri Currency: The term “Miri” is derived from the Persian and Turkish word “Amiri” which is attributed to “Emir”. From this derivation, the terms “Malia” and “Mali” emerged. Al-Mal Al-Miri (Miri Funds) denotes the state’s funds. Reinhart Pieter Anne Dozy, Takmelat Al-Maajim Al-Arabiya, First Edition, Ministry of Culture and Information, Republic of Iraq, 1979-2000, PP. 10/139.

Currency: Refers to the wage for work and cash. Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo, Al- Moajam Al-Wasseet, Al-Da’wah Publishing House. P. 2/628.

The Miri currency is the official currency of the state.

[34] Anwah Al-Jahala: The jurists divided “Ignorance” in contract into two categories:

Major Ignorance: It is the extensive ignorance, i.e. vagueness or ambiguity that cannot be cleared up without adding to the lawsuit’s clauses or changing its content.

Minor Ignorance: It is the vagueness or ambiguity that can be cleared up by clarifying the clauses of the lawsuit’s statement without adding to it or changing its content.

Muhammad Omar Dawud Abu Hilal, Al-Jahala Wa Asarha Fi Al- Da’wah Al-Qadaiya, Academic Book Center, Al-Quds University, 2013, PP. 15-16.

[35] Al-Khubra: In the Islamic context, it refers to knowledge of something or understanding the intricacies of matters. Muhammad Amim Al-Eḥsan Al-Mujaddadi Al-Barkati, Al-Taarifat Al-Fiqhiya, First Edition, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2003, P. 85.

[36] Muayanat: Refers to the inspection of a property to negate any form of ignorance. It signifies a thorough knowledge of what is being sold, ensuring there’s complete awareness and eliminating ignorance. Adel Sharif and Mahmoud Rabih Khater, Al-Wafi fi Siyagh Al-Da’wi Wa Al-Oukoud, Dar Mahmoud, Cairo, 2021-2022, P. 516.

[37] Luzum Al-Mubih Bel Al-Ekhtiyar: Choice means a volition. Linguistically, a volition can be associated with the condition by referring the matter to its type and rationale. As for its compound meaning, it refers to the option to either terminate the sale contract within a designated timeframe or enforce it, all under permissible conditions. This depends on the stipulated condition and its inherent volition, which is fixed and valid in both proper and flawed sales. Elias Matar (the book is translated from Turkish into Arabic), Shareh al-Majalla, First Edition, 1880, P. 74.

[38] Ibraa Zimma: To release the designated person from any debt. Abd Al-Karim Bin Ali Bin Muhammad Al-Namlah, Al-Muhazib fi Eilem Usul Al-Fiqh Al-Muqarin, Al-Rushd Library for Publishing and Distribution, Riyadh, 1999, P. 1398.

[39] Durk (In Islamic jurisprudence): Represents any guarantee provided to the buyer concerning the payment if the sale becomes due, or a guarantee for the sold items to the seller if the price is due. Muhammad Hadi Al-Shamrakhi Al-Mardini, Sharh Al-Allama Al-Shaykh Muhammed Bin Qasim Al-Ghazzi Al-Mosama Fateh Al-Qareeb Al-Mujib Fi Sharh Alfaz Al-Takreeb Lel Imam Al-Allama Ahmed Bin Al-Hussein Al-Shahir bi Abu Shujaa. Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Lebanon, 2016, P. 89.

[40] Tabaeeya (in Islamic Transactions): It is all that is associated with a sale and accompanies it, for example, the garden within the wing’s premises and the buildings established on the land; Everything related to the sale in this context acts as an adjective, and the adjective follows the described matter. Dependence may also include the sale’s necessities; as the sale’s benefits cannot be achieved without it, such as the right of passage and the residence’s facilities. From these examples, it appears that dependence may include physical dependence; however, there is another type of dependence, which is moral dependence, in which the follower is considered a part of the followed morally, not physically, such as the prayer’s dependence on the Imam, the soldiers’ dependence on the commander, and so on. Muhammad Rafi Salem Ali, Tawabii Al-Mubii Wa Kawaidha Al-Fiqhiya, Al-Mukhtar Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 39, No. 1, Libya, 2021, PP. 212-217.

[41] Shohoud Al-Hal: Refers to witnesses who were in attendance or present at a particular place or location. The term “Al-Hal” translates to ‘place’ or ‘location’. Ibn Manzur, Lisan Al-Arab, Dar Al-Maaref, Cairo, P. 972.